10 Aug 2025

Valuation of Cryptocurrency in Relationship Property Disputes

Summary

- Introduction

- Volatility of cryptocurrency

- Principles of valuation

- Volatility and relationship property

- Bypassing valuation

- Circumstances warranting valuation

- Allegedly lost or stolen

- New Zealand case

- Australian cases

- Trivial amount

- Violation of restraining order

- Cryptocurrency-restricted jurisdiction

- Capital versus income

- Non-fungible tokens

- Post-separation contribution and dissipation

- Conclusion

Copyright of the New Zealand Family Law Journal is the property of LexisNexis NZ Ltd and its content may not be copied, saved or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's written permission. However, users may print, download or email articles for individual use.

Article by Jae Lee, a PhD candidate at the University of Auckland, researching the intersection of technology, property, and family law. Jae Lee completed an LLB (First Class Honours) at the University of Waikato and an LLM (First Class Honours) at the University of Auckland, where this article originated as part of his master’s thesis.

Introduction

The South Sea Bubble of 1720 is known as one of the earliest and most extensively studied financial crashes. Among the most compelling stories from this period is that of Sir Isaac Newton, who initially profited from his investments in the South Sea Company but lost most of his fortune when he reinvested at the market’s peak before the crash. Newton’s alleged remark that he could “calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people” reflects the unpredictable nature of financial markets. This remark bears a striking resemblance to the modern, extremely volatile cryptocurrency markets. How can the court measure “the madness of people”? It raises fundamental questions about valuation, particularly, how cryptocurrencies are valued and the factors that can lead to discrepancies.

The term “valuation” means an estimation of the monetary value of a particular property. In the context of the Property (Relationships) Act 1976 (PRA), it is the monetary value of property in a real or hypothetical market. In order to arrive at an accurate and fair assessment, the court must answer two main questions: the quantum and the date of valuation. The task of valuation is relatively straightforward in circumstances where the value is easily ascertainable such as shares traded on a stock exchange. In the absence of a market or where the nature of it makes valuation difficult, ascertaining its value becomes a complex and challenging exercise. The courts in such cases resort to the hypothetical exercise of what “a willing but not anxious vendor would sell and a willing but not anxious purchaser would buy”. This approach implies that the valuation is concerned with the market value. However, given that the nature of inquiry is hypothetical, it has led to numerous disputes in determination of the quantum of the market value, ranging from legal practices, accounting firms, shares, goodwill, superannuation funds, and debts.

Another category of disputes in relation to valuation is whether the presumption under s 2G of PRA in favour of valuation at the hearing date should be displaced. Section 2G is similar to its predecessor, s 2 of Matrimonial Property Act 1976 (MPA). Historically, the courts have used the discretion under s 2(2) of the MPA to value at another date to allow for post-separation contributions by a spouse. This is particularly relevant where the court finds it necessary to ensure justice, especially when the value at the hearing date would allow “one party to benefit unfairly from the post-separation efforts of the other”. In other words, the default position is the value at the hearing date but if it results in substantive unfairness then the court has the discretion to change the valuation date to achieve a fair and just division.

In general, valuations determined at the hearing date are presumed to be fair and equitable. This is based on the premise that parties equally contribute to the product of relationship and the value of that product is to be assessed at current not historical values, to ensure equal sharing. An exception to this is the exclusive use and control of assets post-separation, typically those that depreciate, where valuation at separation is considered appropriate if one of the parties has had post-separation use and enjoyment. For instance, a vehicle may be valued at the time of separation given its usual decrease in value over time. The rationale is that valuing at the hearing date would be unfair if the depreciating vehicle was used by one spouse, only for the other to accept a depreciated value at a later hearing date.

Since the enactment of ss 18B and 18C of the PRA which specifically address post-separation contributions and dissipation, there is less need than in the past for the court to depart from the default position. Originally, the MPA did not specifically account for post-separation contributions or the dissipation of relationship property. This gap left significant room for applying the discretion provided by s 2(2) of the MPA. Sections 18B and 18C were introduced to fill this gap and provide “a specific mechanism for the court to address unfairness which can arise as a result of post-separation events”. Given the scope of ss 18B and 18C is limited to the post-separation period, which is the period of time from the end of the relationship to the hearing date, there appears to be limited circumstances in which the court may exercise its discretion under s 2G of the PRA. For example, in AB v BC, as the value as at the hearing date was nil, the court had to exercise the discretion under s 2G(2) and determine the value of the property in question at the separation date. One notable difference seems to be that exercising the discretion under ss 18B or 18C would result in an unequal sharing only for the post-separation period; and the presumption of equal contribution remains up until the separation date. On the other hand, the discretion under s 2G does not displace the presumption of equal contribution but simply shifts the valuation date. The point is that, as observed by the Court of Appeal, the method of fixing values under s 2G or ss 18B and 18C is ancillary to the fundamental purpose of achieving a fair apportionment.

However, the preceding question before valuation must be whether the asset in question should be sold on the market or vested in one party. This is because valuation only gains its relevance when there is a need to establish the market value and it arises where the court is of the view that one party should be given the right to buy out the share of the other. Valuation ensures that each share of the asset to be given to parties is equitable based on its market value. If the court orders the asset to be sold, then valuation is likely to be unnecessary, because there is an expectation that the sale would determine the accurate market value. Valuation is also not necessary in cases where the court vests the property in both spouses. Thus, the valuation exercise often indicates that the property itself is either indivisible, or that division is undesirable or impractical.

This leads to the question of divisibility of cryptocurrency. Like fiat currencies, most cryptocurrencies are divisible, with the degree of divisibility varying by the specific cryptocurrency. For instance, Bitcoin’s smallest unit, known as a Satoshi, is equivalent to 0.00000001 Bitcoin. Ethereum, on the other hand, offers an even greater level of divisibility, allowing division up to 18 decimal places. Nonetheless, the divisibility of cryptocurrencies does not eliminate the need for valuation in many circumstances. For instance, valuation may be required when the court needs to assess the possibility of asset dissipation under s 18C or when it is impractical or infeasible to order a division of cryptocurrency.

This article aims to answer the following questions: how can cryptocurrencies be fairly and equitably valued for the purpose of relationship property division, given their extreme volatility? And how can the law account for potential fluctuations in value over the course of lengthy proceedings? As a starting point, this article will commence by exploring the challenges involved in the valuation of cryptocurrency.

Volatility of cryptocurrency

One of the biggest challenges of valuation of cryptocurrency is its volatility. The Oxford Dictionary of Finance and Banking defines volatility as “the extent to which the value of a security, bond, commodity, market index, etc. varies over time”.25 When the price remains relatively steady, the asset is considered to have low volatility. If the asset experiences quick surges and dramatic drops, it is considered to be highly volatile.

As of December 2023, there are over 600 centralised exchanges worldwide that can facilitate trading between fiat currency and cryptocurrency pairs such as BTC-USD(Bitcoin to United States dollar), NZD-BTC (New Zealand dollar to Bitcoin) and others.26 This is a stark contrast with the conventional difficulties associated with the valuation of assets without a market, or the inherent nature of property that makes valuation difficult. Given the ample number of centralised exchanges around the world, including New Zealand, it is unlikely that there will be any difficulty in ascertaining the value of cryptocurrency at any given time, or requiring the court to resort to the hypothetical exercise in order to arrive at an accurate estimate of the value.27

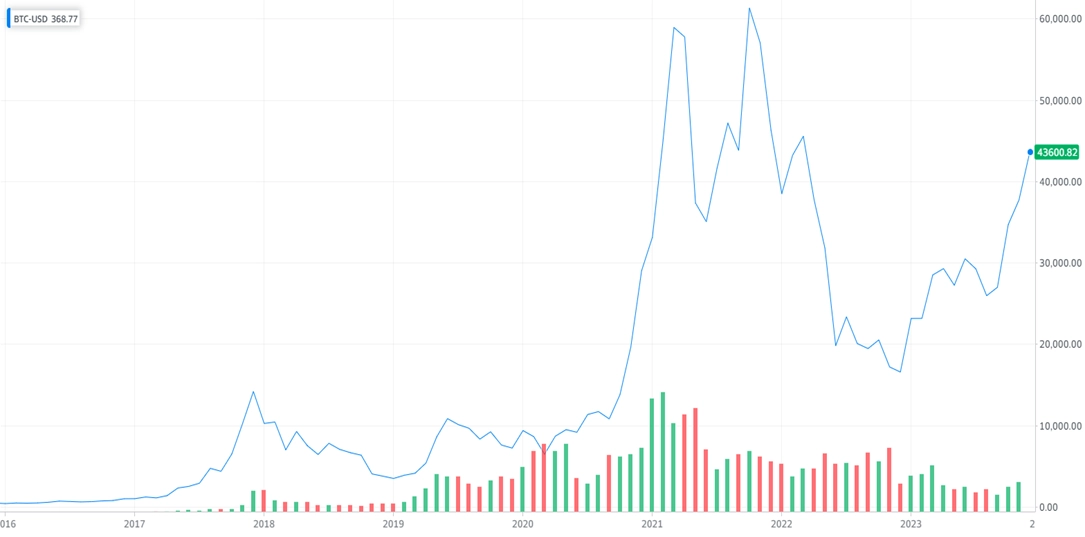

Figure 1: Seven-Year Price Change in BTC-USD Exchange Rate—from approximately $370 on 1 January 2016 to $43,600 on 1 December 2023.

The English case, Tulip Trading Ltd v Bitcoin Association for BSV, demonstrates how the court perceives the volatility and unpredictability of cryptocurrency.28 In that case, the court had to decide the quantum and the manner of security that the claimant has to provide to the court in the event the claim is unsuccessful. The claimant proposed a novel way of security by way of cryptocurrency, with an additional 10 per cent “buffer” to address the volatility issue. The court declined the security offer based on the law requiring the security to be either by payment into court or by a guarantee from a first class London bank; and any alternative form of security must be at least equal to the conventional ways.29 Considering that many conventional assets would not be considered at least equal to a letter of credit issued by a first class London bank, the decision not to accept Bitcoin as a security is not a surprising one. This is particularly so given that the primary purpose of security is to minimise the risk of financial loss. However, in relation to the volatility, it is interesting to note the court’s view on the possibility of Bitcoin becoming valueless:30

It would expose [the defendants] to a risk to which they would not be exposed with the usual forms of security: namely of a fall in value of Bitcoin, which could result in their security being effectively valueless. [emphasis added]

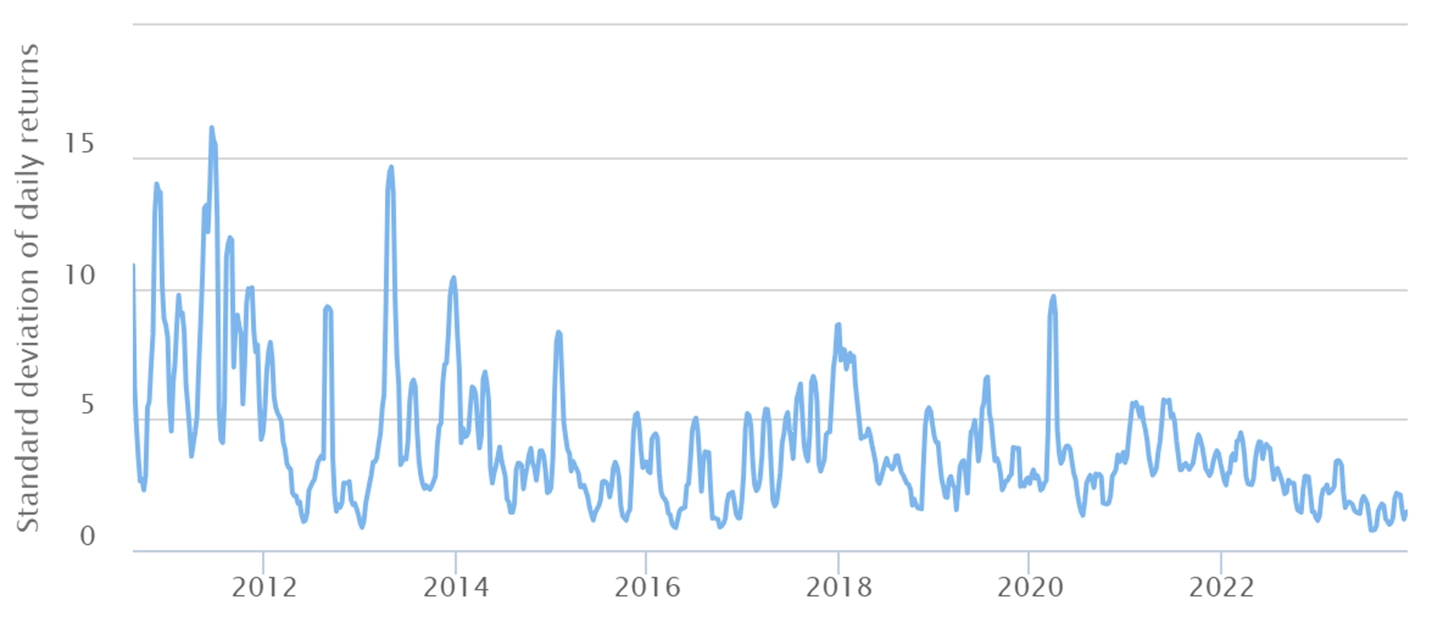

Figure 2: Historical Volatility of BTC-USD — The standard deviation of daily returns for the BTC to USD exchange rate over the past decade (Source: Yahoo! Finance).

Based on the significant increase in the Bitcoin value over the last decade, the English court’s view about the potential fall in Bitcoin’s value which could render the security effectively valueless appears to be at an extreme end, but not without any basis. For example, the period from December 2017 to December 2018 saw a dramatic decline in the price from USD 20,000 to USD 3,200, resulting in an 84 per cent decrease.31 Based on such dramatic falls, it is arguable that the court’s view is based on observable market behaviours. On the other hand, one of the highest surges within a year period occurred between14 March 2020 and 13 March 2021, when Bitcoin’s value increased from a low of USD 5,200 to an unprecedented peak above USD 60,000, yielding a 1,053 per cent increase over the 12-month period.32 Despite extreme short-term price fluctuations, Bitcoin’s value has experienced a remarkable increase in the long term. Over the last seven years, it soared from approximately USD 370 on 1 January 2016, to USD 43,600 by 1 December 2023, marking an astonishing increase of 11,710 per cent (Figure 1).

The extent of Bitcoin’s volatility is visualised in Figure 2 which shows the standard deviation of daily returns over the last decade. While the standard deviation of daily returns appears to be stabilising, maintaining below five per cent for post-2018, nevertheless it retains a much higher volatility compared to traditional assets like stocks or bonds. Considering that the interest rate for a 12-month term deposit with a major New Zealand bank is around six per cent per annum,33 a daily price fluctuation of five per cent is significant. In addition, given that Bitcoin is regarded as the reserve currency among cryptocurrencies, Bitcoin’s volatility is generally perceived as more stable than other cryptocurrencies with smaller market capitalisation. Small market cap cryptocurrencies are generally newer and have yet to establish a strong market presence, but with a lot of potential for growth. On price tracking platforms, observing cryptocurrencies with small market caps spiking or dropping in value by more than 40 per cent within a 24-hour window is relatively common (Figure 3).

Figure 3: “Most Volatile Cryptocurrencies” as of 21 April 2024, ordered by the percentage change in the last 24 hours (https://coincodex.com/most-volatile).

An interesting aspect of Tulip Trading Ltd is that the claimant could have met the legal security requirements by selling the Bitcoin for pounds sterling. This could have been facilitated through a payment either directly to the court or to a bank for a letter of credit. The fact that the claimant proposed an extra 10 per cent over the required amount as a safeguard against volatility risks strongly suggests the claimant had the financial capability to fulfil the legal security requirements. The claimant’s primary motive appears to be to explore the legal boundaries surrounding cryptocurrencies, rather than stemming from any financial constraints.

Setting aside speculations about how the cryptocurrency market will evolve, what is certain from both historical and current market data is that extreme volatility is likely to continue in the foreseeable future. At the same time, it is essential to recognise that volatility is a relative concept, not confined to cryptocurrency. For example, the exchange rate of the New Zealand dollar (NZD) to United States dollar (USD) fluctuates due to various factors, though much less volatile than cryptocurrencies. In recent years, government-issued currencies like the Argentinian Peso or the Turkish Lira experienced high volatility on par with or even exceeding Bitcoin.34 In this respect, cryptocurrencies are not unique and the notion of volatility is a matter of degree. Thus, the following analysis may be applicable to other properties that exhibit a high volatility pattern of a standard deviation of daily returns of five per cent and above.

Principles of valuation

Although the PRA does not specify the principles applied in valuing relationship property,35 the aim must align with the principles and purpose of the PRA.36 The Supreme Court in Scott v Williams stated that:37

If, in the particular circumstances, a different valuation method is appropriate in order to arrive at a fair and just division of relationship property, then that method should be used. The methodology and result in any case reflects the particular circumstances in that case and the particular evidence given. Treating any case as binding precedent on methodology is not appropriate.

The judge should always consider whether the result reached by any particular methodology is fair and just…The essential question is not what is the right valuation method, but what is the right result, being a result that achieves a fair and just division of relationship property.

Although the below excerpt is in relation to s 15 of the PRA, it has some relevance to the understanding the meaning of justice:38

The assessment of what is just is constrained in that it must relate to the evidence of the particular circumstances of the particular couple. A just order should be designed to compensate fully for the disparity but not past the point where it would risk creating a disparity the other way.

Thus, the PRA demands valuation to be substantively fair for both spouses.

Volatility and relationship property

The question, then, is how the volatility of cryptocurrency affects a just division of the relationship property that is substantively fair for both spouses? Does the impact of market fluctuations on cryptocurrency value pose a challenge to the PRA concept of just division?

First, the extreme volatile nature raises a question as to the exact meaning of the date of the hearing. Under s 2G(1) of the PRA, the value of any property is to be determined as at the date of the hearing of that application by the court of first instance.39 This raises an issue of determining which date and time’s exchange rate the court should apply. If the hearing spans over a number of days, which date of the hearing should the court use to determine the value? If a hearing spans over a two-day period, the cryptocurrency’s value could significantly change between the start and end of the proceedings. Even if the hearing is a one-day event, the value can fluctuate within the same day. In other words, the Bitcoin price at 9 am may significantly differ by 5 pm on the same day. For instance, one of the largest one day drops in Bitcoin’s value against USD occurred on 11 January 2021, when the price fell 25 per cent from around $40,000 to lows of $32,000 within a 24-hour period.40 The largest one-day gain for Bitcoin was on 7 December 2017 when the price soared from $16,000 to almost $20,000.41 This problem is exacerbated if the cryptocurrency in question has a small market cap or is among the newer cryptocurrencies that have yet to establish a strong market presence. Such cryptocurrencies could experience fluctuations more significant than those seen in major cryptocurrencies (for examples refer to Figure 3). Moreover, it is worth noting that unlike traditional assets, which are traded on exchanges with specific opening and closing times, cryptocurrency markets operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week, without any breaks. This round-the-clock trading means that cryptocurrency prices can fluctuate at any time of day or night, influenced by a global market of buyers and sellers.

In order to address the volatility issue, the court may adopt a specific method of setting the exchange rate, such as choosing a rate at the close of the market on a particular day or averaging the rates over the days of the hearing. While such approaches may offer a degree of predictability, all of them could significantly impact the fairness of asset division, as the value may fluctuate between the hearing date and the date of judgment. If the price increases or decreases significantly before the decision is released, obeying the decision is likely to be unfair for one spouse at the expense of the other. If one spouse is awarded an amount equivalent to their half share of cryptocurrency based on the hearing date’s value, but by the time the judgment is released to the parties, the value of cryptocurrency has significantly decreased, the receiving spouse will effectively receive less value than intended by the court. Conversely, if the value of cryptocurrency increases significantly after the hearing but before the judgment, the paying spouse may feel the impact of having to part with an asset that is now worth much more than at the time of the court’s decision.

While fluctuations between the hearing date and the judgment date are common for conventional assets too, the degree of volatility is significantly less compared to cryptocurrencies. For instance, the Quotable Value House Price Index indicates that in November 2021, New Zealand experienced one of its largest property price increases; the national “quarterly” average rose by 6.9 per cent, with some areas, such as Christchurch, seeing increases as high as 12.7 per cent.42 In contrast, the value of cryptocurrencies can fluctuate dramatically ranging from three per cent to over 40 per cent “daily”, either positively or negatively.43 Such dramatic fluctuations are rare for conventional assets and typically occur only under extreme economic conditions.

Alternatively, the court may consider setting the exchange rate based on the market rate at a future date, such as the date of judgment or the date when the cryptocurrency is to be liquidated. While this approach appears equitable, it cannot fully mitigate the risks and unpredictability associated with fluctuating market rates either. For instance, suppose the court decides that the amount of cryptocurrency to be divided between the spouses will be valued based on the market rate on the date of the judgment. Suppose the market rate of Bitcoin is $40,000 per bitcoin at the time of the hearing, but by the judgment date, it has risen to $50,000 per bitcoin. The spouse receiving an amount equivalent to their half share of the cryptocurrency would benefit from a significant increase in value, receiving more in actual value than might have been intended by the judgment, at the expense of the other spouse. Conversely, if the market rate drops to $30,000 by the valuation date, the receiving spouse ends up with considerably less value than anticipated.

Second, there are numerous scenarios in which it might appear unjust for one spouse if the cryptocurrency is to be vested in the other spouse and the cryptocurrency’s valuation is significantly higher or lower at the time of the hearing compared to its typical value. This situation can be particularly inequitable if the market change is temporary. For example, as shown in Figure 4, the price of Uniswap, the 24th largest cryptocurrency by market cap as of April 2024, generally varied between $5 and $8.44 However, there was a significant increase of about 120 per cent in February 2024 followed by a sudden drop in April 2024, lasting only about seven weeks. If relationship property proceedings were to be held within this seven-week period, the short-term increase could significantly inflate the asset’s value, only for it to decline shortly thereafter. Such volatility complicates equitable division, as the timing of the legal process could disproportionately benefit one party over the other, based on temporary market conditions rather than the asset’s average value over the longer term. Again, the core issue here is the extreme volatility, which can dramatically skew the fairness of any decisions.

Figure 4: The price movements of Uniswap (UNI) against USD between December 2023 and April 2024 (Source: Binance, TradingView.com).

Unfairness may also arise when the parties enter into an agreement under s 21A of the PRA aiming to resolve disputes outside of the court. Subsequent to such an agreement, significant fluctuations in the value of cryptocurrency may benefit one party while disadvantaging the other. Whether enforcing such an agreement constitutes serious injustice, which would necessitate the court’s intervention, would depend on a case-by-case basis. The Court of Appeal noted that serious injustice often stems from procedural issues that lead to unequal outcomes, rather than from the unequal outcomes themselves.45 Accordingly, the mere presence of volatility is unlikely to justify setting aside the agreement, especially if both parties were fully informed and aware of the risks associated with cryptocurrency’s volatility. However, if one party was not aware of these risks, the change in value could be deemed unexpected or unforeseen, potentially allowing for intervention.46

Overall, from a purely numerical perspective, applying the principle of equal sharing to the cryptocurrency’s value at the time of the hearing, or on another deemed appropriate by the court, appears just and aligns with the aims and purposes of the PRA. This is especially so if the couple understood that investing in cryptocurrency involves significant and exceptional risks arising from its volatility. However, considering the fact that valuation gains relevance only when the court decides that one party should have the right to buy out the other’s share, the extreme volatility of cryptocurrency can make the buyout price cheap or expensive depending on the exchange rate. The party seeking to have the cryptocurrency vested in themselves would hope for the exchange rate to be low on the day of the hearing and the other party hoping for the opposite. Regardless of the date the court selects or how equitable its process for choosing that date may seem, the volatility of cryptocurrency renders the division of relationship property into a lottery. The value of the cryptocurrency on the hearing date could significantly deviate days or even hours before or after the hearing date, making the division of assets unpredictable and potentially unfair.

In addition, if the amount of cryptocurrency in dispute is substantial, a few percent increase or decrease could have a significant impact on the overall amount of division. Consider a situation where a couple is dividing relationship property that include 100 bitcoins. At the time of their relationship property proceeding, if the price of Bitcoin is $50,000 per coin, the total value of the Bitcoin to be divided is $5,000,000. However, due to the volatile nature of cryptocurrency markets, if the price of Bitcoin increases by just five per cent before the division is finalised, the total value would rise to $5,250,000. This five per cent increase translates to an additional $250,000 in value that must be accounted for in the division. On the other hand, a five per cent decrease in the price of Bitcoin would reduce the total value to $4,750,000, potentially leaving the receiving party with $250,000 less than expected. The disparity increases significantly with cryptocurrencies that have small market caps, such as those shown in Figures 3 and 4.

While some may argue that it would be extremely unlikely to find couples with substantial amounts invested into cryptocurrency, such a viewpoint is not accurate. There are couples and families that have their entire assets based on cryptocurrency. For instance, a family in the Netherlands liquidated all their property, including their profitable business and 2,500-sq ft family home, to invest in Bitcoin in 2017.47 Given the substantial appreciation in Bitcoin’s value, their investment is likely to have grown considerably, although the exact amount of their holdings remains undisclosed. If a similar family were in New Zealand, their cryptocurrency holdings, being considered property, would likely be deemed relationship property and subject to the PRA. Given the increasing adoption of Bitcoin by mainstream financial institutions and its astronomical growth over the past decade, it is reasonable to anticipate that this uptrend will continue, attracting more couples and families into the cryptocurrency market. This growing interest and investment in cryptocurrencies are not only limited to Bitcoin but extend to other cryptocurrencies as well. As technology advances and regulatory frameworks evolve, the integration of cryptocurrencies into traditional financial systems is likely to expand further.48

Bypassing valuation

New Zealand courts appear to operate under the presumption that valuation in the context of the PRA is sufficiently certain to determine an appropriate valuation at all times. According to Hardie Boys J:49

I am sure it is possible for a qualified valuer to place a fair figure on a property at a given date. If that were not so, there could rarely if ever properly be orders entitling one spouse to buy out the share of the other.

Similarly, Glazebrook J in Scott v Williams stated that:50

I do not accept that valuations are so uncertain that a court is not able to come to a view on the appropriate valuation to apply for the purposes of s 11(1)(a) of the PRA, whatever the state of the market or however unique the property in question. [emphasis added]

Despite the strong sentiment among judges that valuation possesses a sufficient level of certainty necessary for judicial determination, the volatility of cryptocurrency directly challenges this view. For cryptocurrency, uncertainties in valuation can indeed be so profound as to hinder the court’s ability to establish an appropriate valuation. Even if the valuation appears correct on the day of the hearing, it may not be so when the judgment is handed down. The court is likely to face numerous issues in determining an exchange rate that is equitable to both spouses. As long as the volatility remains, there appears to be no clear answer to these difficulties. However, it does not mean the court can never arrive at an appropriate valuation of cryptocurrency. The extreme volatility does not mean the price fluctuates at all times: on some days the prices may stay relatively steady which would allow reasonably accurate valuations. Furthermore, in light of recent developments such as the introduction of regulated Bitcoin futures in 2017,51 and the approval of the exchange traded funds (ETFs) by the United States securities regulator, the Securities and Exchange Commission, in January 2024,52 the more cryptocurrencies get adopted by mainstream financial institutions, the volatility of cryptocurrency is likely to reduce and slowly stabilise in the future.

Until then, the most pragmatic approach appears to be to bypass the valuation process entirely and divide the cryptocurrency itself. As briefly discussed above, cryptocurrency is highly divisible, making it possible to split these assets without needing to resort to the notional liquidation method of valuation or to convert their value into NZD. This approach addresses the aforementioned issues and risks associated with attempting to assign a fiat currency value to highly volatile cryptocurrencies. Consequently, vesting cryptocurrency to one spouse becomes unnecessary and should be avoided unless there are some special circumstances warranting valuation.53 The division order could simply involve the court instructing the person in possession of the cryptocurrency to divide or transfer a specified share of the cryptocurrency. By adopting this method, spouses are empowered to decide the optimal time, that is the most advantageous or profitable moment to sell their cryptocurrency holdings. The responsibility for the timing and financial outcome of such sales rests with the parties, not the court. This approach ensures a fair division of cryptocurrency assets without unduly benefiting or disadvantaging either party. This may be compared to the division of fiat currencies like USD or Australian dollars (AUD). These foreign currencies can be divided and transferred to their respective foreign currency accounts without the need to convert them into NZD, simplifying the process and mitigating the complexities and uncertainties associated with exchange rates.

However, direct division is not without its drawbacks. While it seems straightforward in theory, it introduces practical issues such as security, privacy concerns and financial risks. Receiving and possessing cryptocurrency requires handling cryptographic keys or using cryptocurrency wallet software, tasks not everyone has the technical proficiency for. This lack of expertise can pose significant challenges for many. Additionally, owning cryptocurrency carries unique risks not associated with traditional assets, such as potential losses due to hacking or forgotten passwords. Transferring cryptocurrencies can also inadvertently expose sensitive and identifiable financial information. In MMD v JAH, these concerns prompted the Supreme Court of Canada to adopt protective measures such as sealing or partial redaction to safeguard privacy.54 However, given the private nature of Family Court hearings in New Zealand and the fact that Family Court publications can be anonymised, the privacy risks appear to be minimal. In addition, not everyone knows how to choose the optimal time to sell their cryptocurrencies, potentially exposing them to further financial risks.

If the party has no knowledge of how to manage their cryptocurrency, or simply wishes to liquidate their entire share without managing it themselves, the court may instruct an over-the-counter trader or a New Zealand cryptocurrency exchange to convert the cryptocurrency into NZD and transfer it into the party’s bank account.55

Circumstances warranting valuation

The fact that cryptocurrency is divisible does not automatically make valuation redundant. In cases such as those where a spouse claims to have lost their cryptocurrency, courts still need to arrive at a fair estimation of its value. Valuation may be based on the purchase price, the value on the date of the hearing or any other date, or any residual value. Although courts may draw adverse inferences from claims of loss, there is no uniform approach, and outcomes vary depending on the facts of each case. In some instances, adverse inferences may be drawn; in others, the lost cryptocurrency is excluded from the assessment if the loss was credibly established as unintentional, or if there is insufficient evidence to substantiate the claim.

It is important to note that almost all the cases examined for this research, which involve cryptocurrency and relationship property, pertain to the loss of cryptocurrency due to various factors such as scams, hacking or theft. These cases will be discussed shortly. While traditional assets can also be lost, it is much less frequent for the courts to assign responsibility for such losses. This discrepancy may not only highlight the vulnerabilities of cryptocurrencies, such as susceptibility to hacking and password loss, but also their potential for concealment in disputes over relationship property. If a spouse lacks detailed knowledge about the cryptocurrency or cannot prove its existence, the other spouse may choose to withhold disclosure and simply claim that the cryptocurrency is lost. This allows the spouse concealing the cryptocurrency to evade an inconvenient line of inquiry and instead shifts the burden of proof onto the uninformed spouse. If one party has cryptocurrencies but denies ownership or does not disclose fully, the burden of proof precedent operates as a presumed fact unless the other party can come up with compelling evidence. As the resolution of these cases depends on the court’s ability to accurately assess the facts, it is crucial for the judiciary to be well-informed about these unique characteristics of cryptocurrency. In addition, courts should not be overly cautious in inferring asset concealment under appropriate circumstances.

Allegedly lost or stolen

In MW v NLMW, evidence showed that the husband spent considerable time learning about cryptocurrency investments and had invested over CAD 100,000 (Canadian dollars) in various cryptocurrencies.56 The wife had taken occasional photographs of online account summaries and one photo showed account balances totalling about USD 42,000. The husband testified that he was not good at trading cryptocurrencies, that several exchanges where he had invested money had gone bankrupt, and that he had ultimately lost all the money invested in these currencies. However, he failed to provide any documentary evidence to substantiate his claim. While the British Columbia Supreme Court rejected the husband’s claim that all cryptocurrencies were lost, it acknowledged his initial total investment of approximately $100,000 and recognised the possibility of some losses; and the court imputed a value of $60,000 to the cryptocurrency accounts. Although the court did not explicitly explain how it arrived at this figure, it seems to have been based on the wife’s evidence of the husband’s account balance, which showed approximately USD 42,000—roughly equivalent to CAD 60,000.

Chao Liu v Junhua Chang is a marital dissolution appeal, which was heard by the Court of Appeals of Washington.57 The appeal was filed by the husband against an order that involved the distribution of property following the couple’s divorce. One of the contentious issues of the appeal concerned the bitcoins held by the husband. The wife presented evidence showing the husband’s ownership of Bitcoins: a photograph of the husband’s computer screen displaying his wallet containing 53.21 bitcoins valued at approximately $504,766 at that time; and further evidence showing screenshots of transactions from an email dated May 2018 showing the same amount of Bitcoins but valued lower. The husband claimed that the Bitcoin wallet balance was zero at the time of the trial and argued that the software the wife used to show the Bitcoin holdings was obsolete and no longer functioning correctly by the time he transferred and sold the Bitcoins. The court found the husband’s claims not credible due to significant discrepancies in his accounts and lacked the necessary evidence to support his claim on appeal. Accordingly, based on the wife’s evidence, the court found that the husband’s Bitcoins still existed. However, despite the court’s finding that the husband’s Bitcoins still existed, it faced the conundrum of distributing the allegedly non-existent cryptocurrency. Thus, the court valued the Bitcoin at $328,903 as of the trial date, awarded it to the husband, and compensated the wife with a greater share of other assets.

New Zealand case

Beck v Wilkerson appears to be the first known case in the Family Court concerning the division of cryptocurrency in a relationship property dispute.58 Both parties blamed each other for the disappearance of the iPhone 4, which was used to access a cryptocurrency wallet. There were accusations from each side suggesting the other might have accessed the electronic wallets and cashed in the cryptocurrency. However, the court found that evidence provided was insufficient to support the claims made by either party. As a result, it remained unresolved who actually lost the wallet. The court was unable to make a finding on the balance of probabilities that either party was responsible for the loss of the iPhone 4. Thus, the court made no specific allocation, and the cryptocurrency remained allegedly inaccessible and undivided as jointly owned property. If one of the parties was indeed concealing the wallet, as both have alleged, their attempt to hide relationship property went undetected.

Australian cases

In Fallins v Fallins, the husband withdrew $100,000 from a joint account post-separation to purchase cryptocurrency, later reporting it lost due to a scam.59 The court criticised the husband’s investment in cryptocurrency as a significant waste of joint funds, particularly scrutinising his conduct for not disclosing this investment in his affidavit; it was only revealed during cross-examination. The court noted that the husband treated the funds used for buying Bitcoin as his own money despite them being marital assets. Regardless of whether the claim of a scam was genuine, the court ruled the husband had misappropriated joint funds, and thus the lost amount was considered part of his share of the assets. It ruled that he had benefited from the full amount, that is the lost $100,000 representing the original invested amount, concluding that the full amount of the original investment was to be included in his asset pool. The court appeared to have two options: first, valuing the lost Bitcoin as of the date of the hearing, reflecting its current market value; or second, using the initial investment value. In this particular case, considering that the first option could have resulted in the value of Bitcoin being lower or higher than the initial investment, the court’s decision to use the initial investment amount seems more equitable for both parties. However, depending on the specifics of the case, courts should nonetheless evaluate all options and make a decision that is substantively fair for both parties.

In contrast, in Wade v Alawi, the husband withdrew approximately $275,000 from the couple’s mortgage to invest in Bitcoins without consulting his wife.60 He subsequently lost most of this investment when the market crashed in 2018, with only about $6,000 remaining. The wife argued that the husband’s investment in Bitcoin was completely reckless and had significantly reduced the equity in their home. The husband countered, suggesting that had the investment been profitable, the wife would have claimed a share of the profits. The court found that it is not a case where the husband had deliberately wasted funds and although the failed investment has diminished the asset pool, the loss was unintentional. Given that any profits, if they had existed, would have been considered in the adjustment of the parties’ property interests, the court held that both parties should share the losses incurred as a result of the failed investment in Bitcoin. Considering that the husband made the investment decision unilaterally without informing the wife, thereby impeding her ability to exercise her rights or make informed decisions about the investment, the court’s ruling that the wife should also bear the loss equally seems harsh.

Roswell v Roswell involved a dispute regarding cryptocurrency that the husband allegedly owned.61 The wife claimed that the husband had invested significant sums in cryptocurrency, specifically $25,000 and then an additional $10,000. However, the husband disputed these amounts, stating that he had actually invested only $10,000 and $3,000 and had lost these sums. Given the conflicting evidence and the husband’s claim that the invested sums had been lost, the court was unable to verify the existence or current value of the investment and decided not to include the cryptocurrency in the parties’ pool of assets.

Trivial amount

In cases where one party discloses a relatively trivial amount of cryptocurrency, it often goes undisputed by the opposing side or excluded from the relationship property pool like in Roswell v Roswell.62 Similarly, in Macvean & Manton (No 2), the wife alleged that her husband invested about AUD 2,656 in cryptocurrency.63 The husband argued, saying he no longer possessed any. Given the trivial amount and the wife’s lack of challenge to the husband’s claim, the court chose not to factor in the cryptocurrency in the relationship property pool. The court has chosen to treat the amount in question as insignificant.64

A similar approach has been adopted in New Zealand as seen in the ruling of Biggs v Biggs where the Court of Appeal held that “discovery should be proportionate to the subject- matter”.65 However, such an approach requires careful consideration. First, the judiciary must recognise that cryptocurrency is a relatively new asset class, meaning that every decision, regardless of its scale, can set a precedent for future disputes. The court might benefit from establishing clear guidelines early on. Second, the volatile nature of cryptocurrency means its value can skyrocket in a short period. In Macvean & Manton (No 2), the couple separated in August 2018 and the hearing was in September 2022. During the period, Bitcoin’s value approximately soared 280 per cent from USD 7,000 to USD 20,000. As of writing this article, July 2024, Bitcoin is being traded at around USD70,000. A cryptocurrency deemed trivial today might become significant in the future, and not considering it on the basis of its trivial amount might lead to potential injustices later. Lastly, the principle of just division remains.66 By ignoring even minor assets, the court might inadvertently favour one party over the other and incentivise parties to hide or downplay the significance of cryptocurrencies. One of the core principles of the PRA is that relationship property disputes “should be resolved as inexpensively, simply, and speedily as is consistent with justice” (emphasis added).67 It emphasises that the pursuit of justice should not be mired in protracted legal battles that consume time, money and emotional stress, especially when the sums in question are small relative to the overall property pool. While the principles of the PRA provide guidance to ensure that relationship property disputes are managed efficiently, efficiency cannot prevail over justice and fairness:68

… it has frequently been recognised that the objective of efficient administration of the Court’s business must not be permitted to prejudice a party’s right to a full and fair disposition of his or her cause. The dictates of fairness must prevail over the demands of efficiency. [emphasis added]

Accordingly, it is essential for the courts to adopt a slightly varied approach when dealing with cryptocurrencies, weighing both the immediate efficiencies and practicalities, and at the same time bearing in mind the longer-term implications.

Violation of restraining order

In Lescosky v Durante, the husband transferred a total of $180,000 to acquire cryptocurrency over an 11-day period, violating a restraining order that prohibited him from disposing of any assets.69 A few days after these transactions, a burglary at his parents’ residence resulted in the loss of all his cryptocurrency holdings, including the details of the acquired assets. Recognising the blatant breach of the restraining order, the court imposed a fine of approximately $60,000 on the husband. As the focus of the proceedings was primarily on the imposition of fines for the husband’s contraventions, it is unclear whether the court made any specific orders or awards to the wife regarding the lost cryptocurrency.

In Powell v Christensen, the husband withdrew $25,590 from a joint bank account and $75,000 from his business account to invest in cryptocurrency, violating a restraining order.70 When the court later requested documents to verify the number of bitcoins he owned, the husband failed to produce any. During the trial, he claimed that the value of his cryptocurrencies had declined, estimating his personal holdings at $9,145 and his business holdings between $35,000 and $38,000. Given the lack of evidence except for the bank records of the initial withdrawals, the court decided not to assume a decrease in value. Consequently, it ruled that it was just and equitable to add back the original investment amount, holding the husband accountable for any loss in value.

Cryptocurrency-restricted jurisdiction

In Ruscoe v Houchens, the high-profile liquidation case of Cryptopia Ltd, the High Court addressed several issues arising from the distribution of cryptocurrencies and other assets held by Cryptopia.71 One of these issues was the distribution of cryptocurrencies to users in jurisdictions where the transfer of cryptocurrency could constitute a criminal offence. These jurisdictions include Afghanistan, Algeria, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Egypt, Morocco, Nepal, the People’s Republic of China, Ecuador and Vietnam. The court directed the liquidator to convert the cryptocurrencies into fiat currency and transfer the funds to bank accounts nominated by the account holders. Similarly, in relationship property cases involving a spouse residing in one of these jurisdictions, employing the notional liquidation method to convert cryptocurrencies into fiat currency would be a sensible approach.

Capital versus income

In ME v KK, the Ontario Court of Justice was tasked with assessing the husband’s income, including his cryptocurrency holdings, for child and spousal support purposes.72 The husband claimed that his cryptocurrency account had depleted to minimal monetary value. However, evidence during cross- examination uncovered a $15,000 deposit into his personal bank account from an undisclosed cryptocurrency transaction. Additionally, he could not explain another $10,000 deposit. Based on these transactions, the court inferred that the husband continued to engage in cryptocurrency trading throughout 2020. Yet, due to the highly speculative nature of this income, it was considered non-recurring. Since the focus was on income assessment rather than property division, no valuation of the cryptocurrency was necessary.

The classification of cryptocurrency as either capital or income varies by jurisdiction and is influenced by specific tax laws. For example, in Australia, disposing of cryptocurrency at a profit triggers a capital gains tax unless the gains have already been taxed as income.73 In New Zealand, individuals and businesses must file a tax return when generating taxable income from cryptocurrency activities.74 In other words, similar to conventional property, the proceeds from selling or exchanging cryptocurrency are taxable. Cryptocurrencies also have GST implications in New Zealand when used as payment in standard business activities.75

Non-fungible tokens

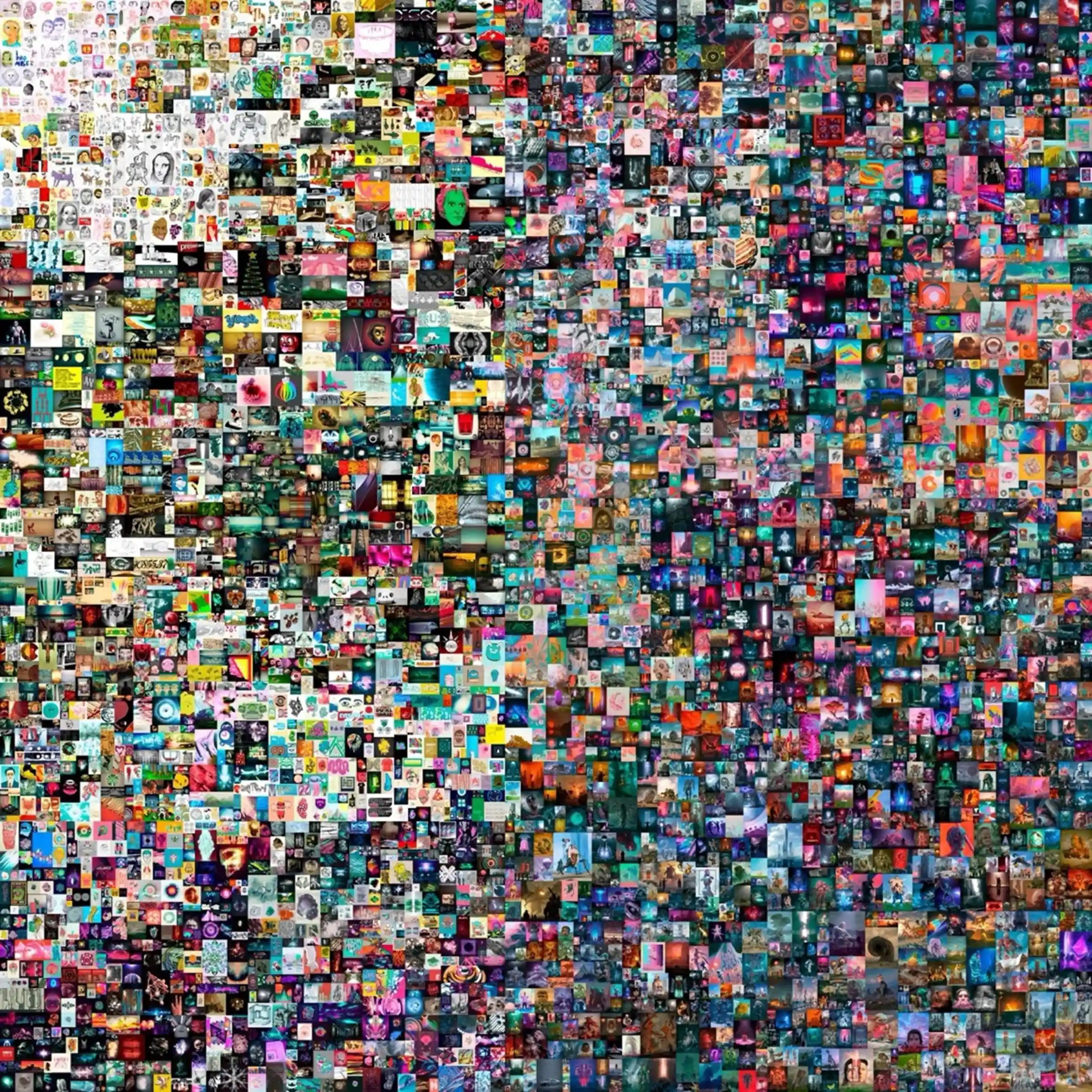

While non-fungible tokens (NFTs) fall under the broad category of cryptocurrencies, as they rely on Distributed Ledger Technology, they are distinctly different from general cryptocurrencies in terms of utility and functionality. Unlike cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, which are digital representations of value or rights that are fungible and interchangeable, NFTs are non-fungible, meaning each one is unique. This uniqueness is similar to how a painting differs from prints of the same artwork. Each NFT represents a unique digital asset on a blockchain, such as digital art, music, videos, and other forms of digital media. For an example of an NFT, see Figure 5. Just as no two original paintings are exactly alike, no two NFTs are the same. For instance, consider Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci; it is valuable not just for the image it portrays but for its authenticity and originality. Similarly, an NFT is valued for its unique properties and cannot simply be exchanged for another similar item, unlike monetary units where one dollar or one bitcoin is equivalent to another of the same. Consequently, the market value of one NFT differs from another, and they cannot be exchanged on a like-for-like basis. NFTs bear more resemblances to tangible assets, warranting the court to resort to the liquidation method of valuation.

Figure 5: “Everydays: The First 5000 Days” by Beeple. This digital artwork was sold for a record-breaking $69 million at a Christie’s auction, making it one of the most expensive NFTs sold to date. (Source: Christie’s post on X, previously known as Twitter).

Post-separation contribution and dissipation

Another issue arising from valuation of cryptocurrency is whether there can be any post-separation contribution. In Burgess v Beaven which concerns a division of real properties, the Supreme Court stated that:76

The Courts used the s 2(2) [of the MPA] discretion to value property otherwise than at hearing date primarily to allow for post-separation contributions whether positive (debt reduction, property maintenance or improvements) or negative (reduction in the value of the property as a result of the actions of one of the partners). The general approach, however, was that hearing date values were conducive of equity and in particular that both parties should usually share increases in values associated with inflation (as opposed to personal effort). [emphasis added]

The term “inflation” used by the court is not merely referring to the economic concept. Rather, the court focuses on whether the change in value can be attributed to one’s “personal efforts”. There appears to be no unified term referring to this concept but commonly referred to as “passive”, “spontaneous”,77 or “changes due to external factors”.78 Section 18B(2) of the PRA reads:

If, during the relevant period, a spouse or partner (party A) has done anything that would have been a contribution [emphasis added] to the marriage, civil union, or de facto relationship if the marriage, civil union, or de facto relationship had not ended, the court, if it considers it just, may for the purposes of compensating party A—

(a) order the other spouse or partner (party B) to pay party A a sum of money:

(b) order party B to transfer to party A any property, whether the property is relationship property or separate property.

From the wording of s 18B(2), the key aspect is not necessarily the consequence or the tangible result of the actions but the nature of the actions themselves.79 For instance, this could include paying off debts, maintaining property, or other non-monetary efforts that would have benefited but may not necessarily result in increase in value. Accordingly, the PRA allows post-separation contribution, but any changes in value beyond personal effort cannot be a basis to displace the hearing date presumption.

What can qualify as personal efforts in the context of cryptocurrency? Consider an imaginary couple, John and Jane, who were married for 10 years before separating. A few years prior to their separation, they invested their savings in Bitcoin by purchasing 10 bitcoins through a registered Financial Services Provider operating in New Zealand. Before making the investment, John and Jane had done their due diligence and understood that Bitcoin can be very volatile and the financial losses can be substantial. At the time of their separation, one bitcoin was valued at $10,000, totalling their investment to $100,000. Shortly after their separation, Jane’s friend Emily, a fund manager, warned her about the potential for a significant drop in value in the near future. This conversation made Jane sceptical and pessimistic about the Bitcoin investment, leading her to demand an immediate return of her 50 per cent share. On the other hand, John, with strong faith in Bitcoin’s future, remained optimistic and opposed liquidating the Bitcoin investment. His faith was based on the recent introduction of regulated Bitcoin futures at the Chicago Board Options Exchange and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. He also believed that Bitcoin will be adopted by major financial institutions in the future which would drive the Bitcoin price up. The couple’s post-separation property negotiations, including the Bitcoin investment, were complicated by their emotional turmoil, preventing them from reaching an agreement. A year later, at the time of the hearing, the price of Bitcoin had doubled to $20,000 per bitcoin, increasing the total value to $200,000. John wanted the Bitcoin investment to be vested in him. In the court, John contended that s 2G presumption should be displaced, adjusting the valuation date of their Bitcoin investment to their separation date. Alternatively, he sought compensation under s 18B for the post- separation contribution, arguing that his decision to retain rather than sell the Bitcoin was an investment choice that led to the post-separation gain, which he claimed should be his. Jane, on the other hand, argued against displacing the presumption, attributing the increase in value not to John’s personal efforts but to general market inflation.

In the context of John and Jane’s Bitcoin investment, can the increase in value be attributed to John’s effort in preserving and resisting liquidation of their investment? In Meikle v Meikle, the husband deserted the family, leaving the wife with their home and three young children.80 The court held that the wife’s post-separation contribution to the property, the mortgage and other property expenses in the family home unaided by the husband after his desertion, can be taken into account under s 2(2) of the MPA. Cooke J described the wife’s contribution as:81

…[the wife] has preserved a home from a forced sale, which might not realise the full value of the property, is entitled to some recognition. And while the joint investment of the parties is kept in real estate its nominal value is likely to keep pace with inflation better than some other forms of investment. Land tends to appreciate in true value, as the community develops. In practice it will not usually be possible to disentangle these elements. The best that the Court can do is to make some reasonable allowance to compensate a spouse who, after the breakdown of the marriage, has done more than her (or his) share in preserving the property or improving it. [emphasis added]

Similarly, Henderson v Drew approached the question of “personal effort” in relation to a dispute over the division of a family home.82 The husband abandoned the home for about three years subsequent to separation. One of the main issues was the valuation date of the family home and the wife argued for the home to be valued at an earlier date when the husband left. Following Meikle v Meikle, the court held that the family home be valued as at the date when the husband left, and the subsequent increase in value of the home be apportioned 7:3 in the wife’s favour.

The cases discussed above demonstrate how it is unjust to divide the post-separation increase in value equally when it can be sufficiently attributed to the efforts of one spouse. Although the discretion is wide and the court needs to consider a broad range of factors in these decisions, it is arguable that John’s determination to retain the Bitcoin, despite Jane’s demand for liquidation, aligns with the principle of recognising post- separation contributions. Typically, nominal increases in value due to market factors are shared equally.83 However, considering that the intent of John’s determination to keep the investment was to increase the value of their investment, the doubling in value could be seen as a direct result of John’s personal effort. The case would be strengthened if John not only resisted from selling the Bitcoin holdings but also actively engaged in trading — purchasing when the prices were low and selling when they were high.

Conversely, if the value of Bitcoin had significantly decreased due to John’s insistence on not liquidating, it prompts the question: could such a loss be attributed to John’s actions? Contributions made post-separation can lead to both gains and losses.84 However, the crux of the matter lies not in the outcome but in the nature and intent behind the contribution. Section 18C(2) of the PRA states:

If, during the relevant period, the relationship property has been materially diminished in value by the deliberate action or inaction [emphasis added] of one spouse or partner (party B), the court may, for the purposes of compensating the other spouse or partner (party A),—

(a) order party B to pay party A a sum of money:

(b) order party B to transfer to party A any property, whether the property is relationship property or separate property.

Although the section does not explicitly require an assessment into a spouse’s intention, the Court of Appeal in GFM v JAM interpreted the term “deliberate” in s 18C(2) as an action or inaction taken with the “intention” of diminishing the value of relationship property:85

The word “deliberate” in s 18C(2) must surely necessitate that party B acted or failed to act intending to diminish the value of relationship property. We do not consider the word “deliberate” refers simply to party B’s action or inaction. Where, prior to division of relationship property, a party continues to deal with that property with no intention to diminish its value, it would be unjust that s 18C operate to penalise that party. [emphasis added]

The Supreme Court implicitly concurred with the Court of Appeal’s decision by declining to grant leave for a further appeal.86

Consequently, if John’s efforts to avoid liquidating their cryptocurrency investment were aimed at increasing its value, they are unlikely to be considered as intended to diminish the property’s value. Investments, whether in cryptocurrencies, stocks, bonds or foreign currencies, inherently carry risks. The primary objective of any investment is financial gain. Therefore, trading, investing or retaining an investment in anticipation of an increase in value cannot be construed as a deliberate attempt to diminish its value. Jane might contend that John’s decision to retain the investment was reckless, given the high volatility of cryptocurrencies. However, recklessness does not equate to deliberateness, although the line between them can be thin and subjective. The court’s evaluation of investment decisions, particularly in the volatile cryptocurrency market, may involve examining the timing, context and rationale behind those decisions, alongside the couple’s overall financial strategy and mutual understanding of the risks. However, as discussed above, ss 18B and 18C of the PRA focus on the “intention” behind the action or inaction related to the asset, rather than the consequences of such decisions. Even if the decision to invest is deemed reckless due to the market volatility, the outcome could have resulted in either a significant gain or a significant loss. Thus, a decision made with the aim of realising a profit, especially within the context of informed and joint decision-making, may logically lead the court to exercise discretion under s 18B but not under s 18C.

However, this raises a complex issue—evaluating a party’s intention behind investment decisions typically only yields rational justifications. It is irrational to assume that an investment is intended to devalue an asset. In defence, a party may reference market trends, financial advice or the pursuit of long-term financial security, aligning their actions with widely recognised and accepted principles of investment and risk management. Consequently, even if a spouse has an ulterior motive to devalue the relationship property, s 18C is unlikely to be invoked unless there is clear evidence of intent to diminish the asset’s value. Although it is desirable for the court to scrutinise the specific circumstances including the financial results of such decisions, s 18C does not seem to allow the court to base its decision beyond the demonstrated intent. Logically, the high threshold set by s 18C may inadvertently create an environment where, post-separation, hiding cryptocurrencies by claiming they were hacked, lost or stolen, is not only possible but potentially facilitated. This is because the burden of proof for demonstrating intent remains high. Despite the limited number of cases concerning cryptocurrency in the context of relationship property, nearly all of them involve claims related to hacked, lost or stolen cryptocurrencies. This disparity highlights a gap that warrants further study.

Conclusion

Given the rapid growth and development, there is substantial room for discussion and a diversity of viewpoints surrounding these topics. With this in mind, this article has arrived at the following key conclusions:

- The extreme volatility of cryptocurrency directly challenges the judicial consensus that valuation in the context of the PRA possesses a sufficient level of certainty required for judicial determination.

- The most pragmatic approach is the direct division of the cryptocurrency itself, without resorting to the notional liquidation method of valuation or converting its value into NZD. This approach mitigates the various issues and risks associated with assigning a fiat currency value to highly volatile cryptocurrencies.

- The majority of the examined cases involving cryptocurrency and relationship property stem from the loss of cryptocurrency. While traditional assets can also be lost, such occurrences are considerably less frequent. This discrepancy not only highlights the vulnerabilities inherent in the digital nature of cryptocurrencies but also their potential for convenient concealment in disputes over relationship property. As the resolution of these cases depends on the court’s ability to accurately assess the facts, it is crucial for the judiciary to understand the unique characteristics of cryptocurrency and not be overly cautious in inferring asset concealment under appropriate circumstances.

Please refer to the PDF version of the article for footnotes

This article is part of the New Zealand Family Law Journal. To enquire about a subscription to the New Zealand Family Law Journal for your law firm, please submit the form below: